No one would ever accuse me of being a little ray of sunshine. I am friendly, smile easily, have what my spouse calls “resting nice face,” but I am constitutionally pessimistic. I think the world is generally a pretty difficult place to be and rather full of needless suffering. I don’t suggest that this is a pleasant or effective manner in which to navigate one’s life, but like the speaker in that Maggie Smith poem, it seems rather baked into my stars. On my first day alive, there was a bomb scare at the hospital.

This said, gloomy little stormcloud I am, I don’t think we’re allowed to abandon each other or abandon the beautiful, heart-breaking chaos of the world. It matters how we show up to greet it.

I started perfecting newborn swaddles early. I graduated from college with a keen interest in women’s health and began applying to midwifery programs. I ordered a few textbooks and (ironically) the chapters on suturing left me queasy. I trained as a doula to see if I could get over my squeamishness and worked as a professional birthworker for almost ten years. I was based in the western PA rust belt—specifically, eleven zip codes chosen for intervention because of their high rates of infant mortality. In these areas, even with world-class research hospitals, maternal-fetal medicine experts and NICU’s, the maternal mortality rate for women of color resembled that of women in non-industrialized nations. I attended not-quite a hundred births, something close to that. Embarrassingly, I lost count. As a doula, you are intimately connected to the new family in the very moments it’s being born. You make a plan for how that baby’s going to eat, wrap ‘em up in swaddling clothes and you head for the door.

Eventually, the first babies I’d welcomed into the world would grow up. I was living in Vermont now and my facebook feed lit up with a news story. A policeman shot and killed an honors student. The student panicked during a traffic stop near my old neighborhood. His last name was familiar. It turned out not to be one of “my babies,” but it easily could have been. I had been raising my own family and hadn’t been adding up the years enough to notice that the other babies—the ones I’d first swaddled—were about to step into their own adult futures. The world they were entering was deeply unsettling.

Part of how you endure as a birthworker (or in any caretaking profession, for that matter) is to focus on the small part you can do, not what you can’t. You can make sure there’s food in the house the day you visit. You can’t ensure their heat will stay on. You do a fair amount of internal boundary work to compartmentalize and soothe your own feelings of powerlessness, horror or doubt about the prospects of any new beginning. You develop a relationship to hope that is not optimistic, but a pragmatic stance—accepting that you don’t know what will happen. It might not work out. It also might, in fact, sometimes it does. Also, whatever happens, it will likely not be any one single moment’s fault or reward. There is not confidence in any one outcome, but an openness to possibility and all the weirdnesses of the world.

This is the kind of hope that Rebecca Solnit described in her essays that formed the basis for Hope in the Dark:

“Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognise uncertainty, you recognise that you may be able to influence the outcomes – you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists adopt the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting. It is the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand. We may not, in fact, know them afterwards either, but they matter all the same, and history is full of people whose influence was most powerful after they were gone.”

As a doula, I arrived at every single birth with the knowledge that I did not know if a baby would be born alive or not. Certainly, everyone in the room wanted them to be.

That’s the deal you make with the universe. You can go to the birth. Go and be deeply invested in the outcome and fully present. You can bring all your skills to the table and practice an exquisite ethic of care. You don’t get to know what’s going to happen next.

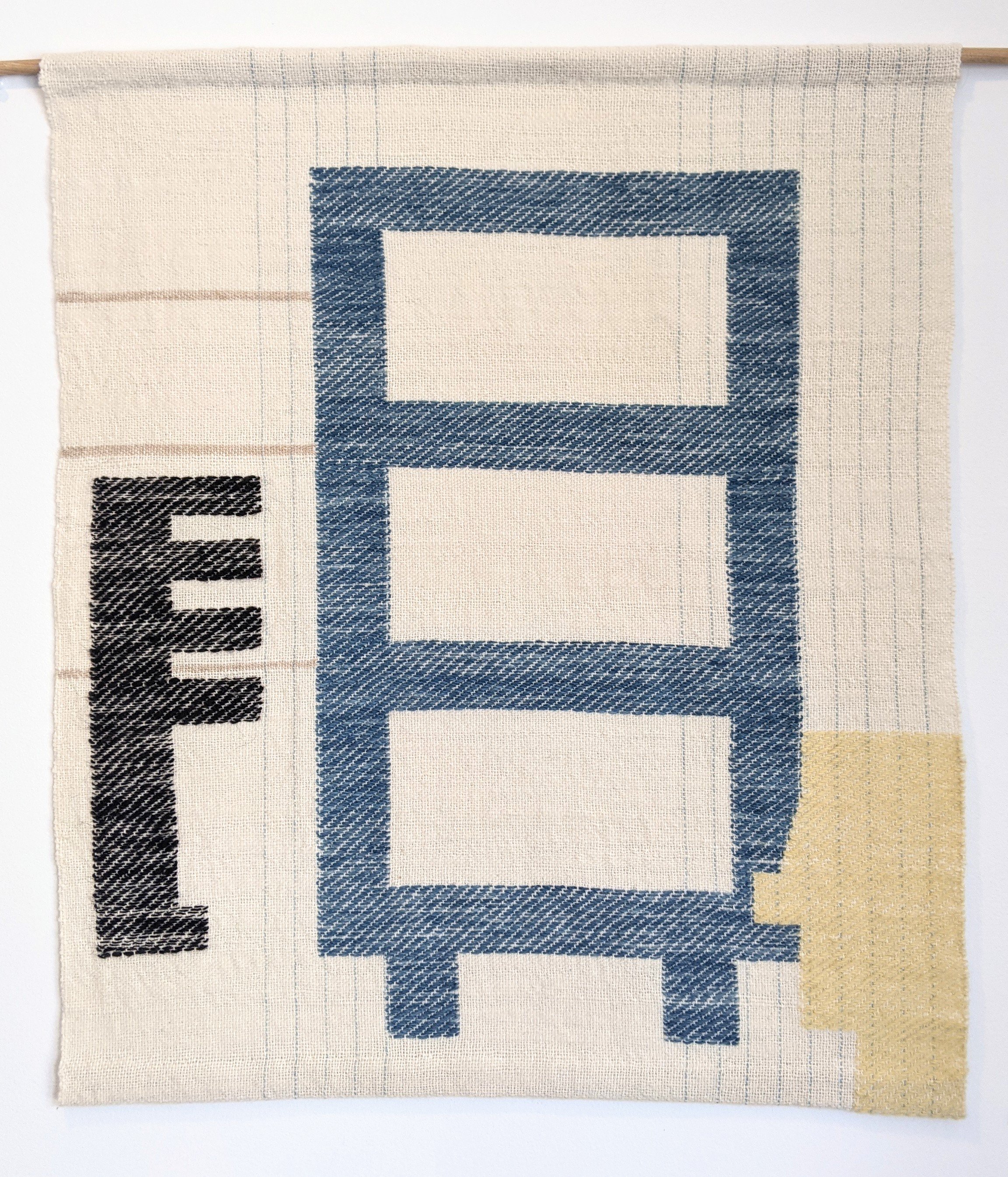

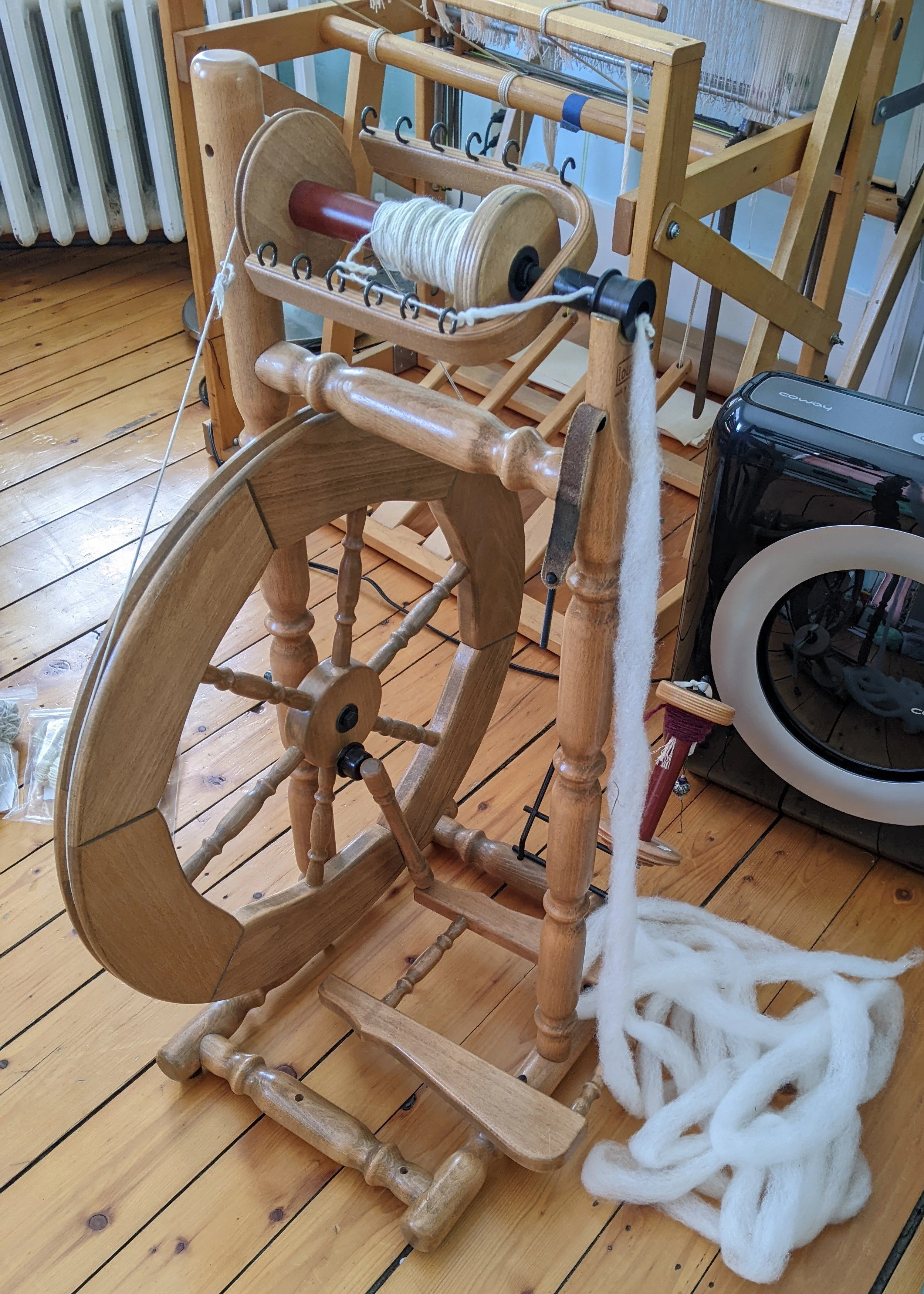

And I desperately want to know what’s going to happen next. When I turn on the news, when I pick up my kid from school—every moment, I’m bracing for the next thing. I want to know if its going to be okay, if the choices were the right enough, the gambles sensible. My friend and their spouse look at their baby and desperately want to know what to prepare them for. You don’t get to know. I sat wriggling in this tension for almost a full year before I turned to weaving objects as a method of holding the contradiction.

The way you greet an unknowable future is to just keep greeting it. And how should you welcome any new thing that is so precious and full of possibility? Say hello, notice the contours, the fingers and toes, wrap it up in the best of whatever you’ve got on hand. You’ll probably need some receiving blankets.