What are we making? A small blanket, probably roughly 30” x 30”—the standard size for a newborn receiving blanket, the most common form of swaddling clothes currently used in the US. I’ve been weaving receiving blankets for about three years now, for reasons I’ll write about in a future post. What will this one look like? Don’t know yet. That’s why we start with spinning, to get the hands busy and open up a clear channel in the psyche to begin imagining the possibilities and questions I want to play around with in this next blanket.

Most modern studio weavers do “recipe weaving,” meaning they take a preexisting design called a weaving draft, modify it a bit and then begin to thread their looms (called warping or dressing the loom) according to the recipe. Some folks do their own designs from scratch and map out on graph paper what happens within each grouping of threads to envision a design before they start to lay the threads in. These weavers begin the process with a sense of what the completed cloth will look like. Because I was trained as both a conceptual artist and a traditional craftsperson, I begin differently from most weavers I know. I don’t start with a design in mind. I starting with a material and often a materials-based question or concept. Right now, the most basic question knocking around in my head—both in terms of the material in front of me and a “big picture” question—is how did all this stuff get here? And I wonder and imagine and then I start to spin.

Right now, I’ve got this Clun wool from sheep raised about 25 minutes from here—a breed that only crossed the Atlantic in 1959—and a batch of other small hanks of yarn spun from heritage breeds from the UK. These breeds are typically raised in small numbers, living pretty close to the place where generations of their genetic ancestors lived. Some of these rare heritage breeds, as James Rebanks explains in his book The Shepherd’s Life, have sheep-y bloodlines meticulously documented and are considered such unique local treasures that vials of their (to put it politely) genetic material are prohibited from transport outside their regions. So while I’m spinning, I’m thinking on a sense of place, about rootedness, about this idea of authenticity. Who or what gets to leave? Who gets to stay and what is the significance and cache of a plant or animal species that is described by ecologists as ‘native.’ I certainly see a special twinkle in a gardener’s eye when they explain to me that a certain plant or section of the garden are all ‘native species.’

I often think about these topics around Town Meeting Day, where local chatter about authenticity and native and who’s “from here” and who’s “from away” tends to reach its annual fevered peak. What does it mean to be from a place? I consider how I can tell a story of my own history where I can sound “from here” or “from away,” depending on my audience and my objectives. I can talk about what civil war battalions my Green Mountain ancestors fought in and mention stone quarries. I could also just say grew up in New Jersey. I meander over to the concept of genetics and the idea of documentation of genetics. Some of these sheep can be traced back much further than my documented family origins. I think about about histories and who gets to access to information about what a family tree looks like, think about who doesn’t have the privilege of that documentation. I think about the weirdness of things like genetic testing and 23andMe or those other genetic testing services that offer up a kind of documentation about being authentically “from” someplace, just like this wool. They’re concepts, histories, stories—but not fictions, right? Maybe there’s a little bit of fiction?

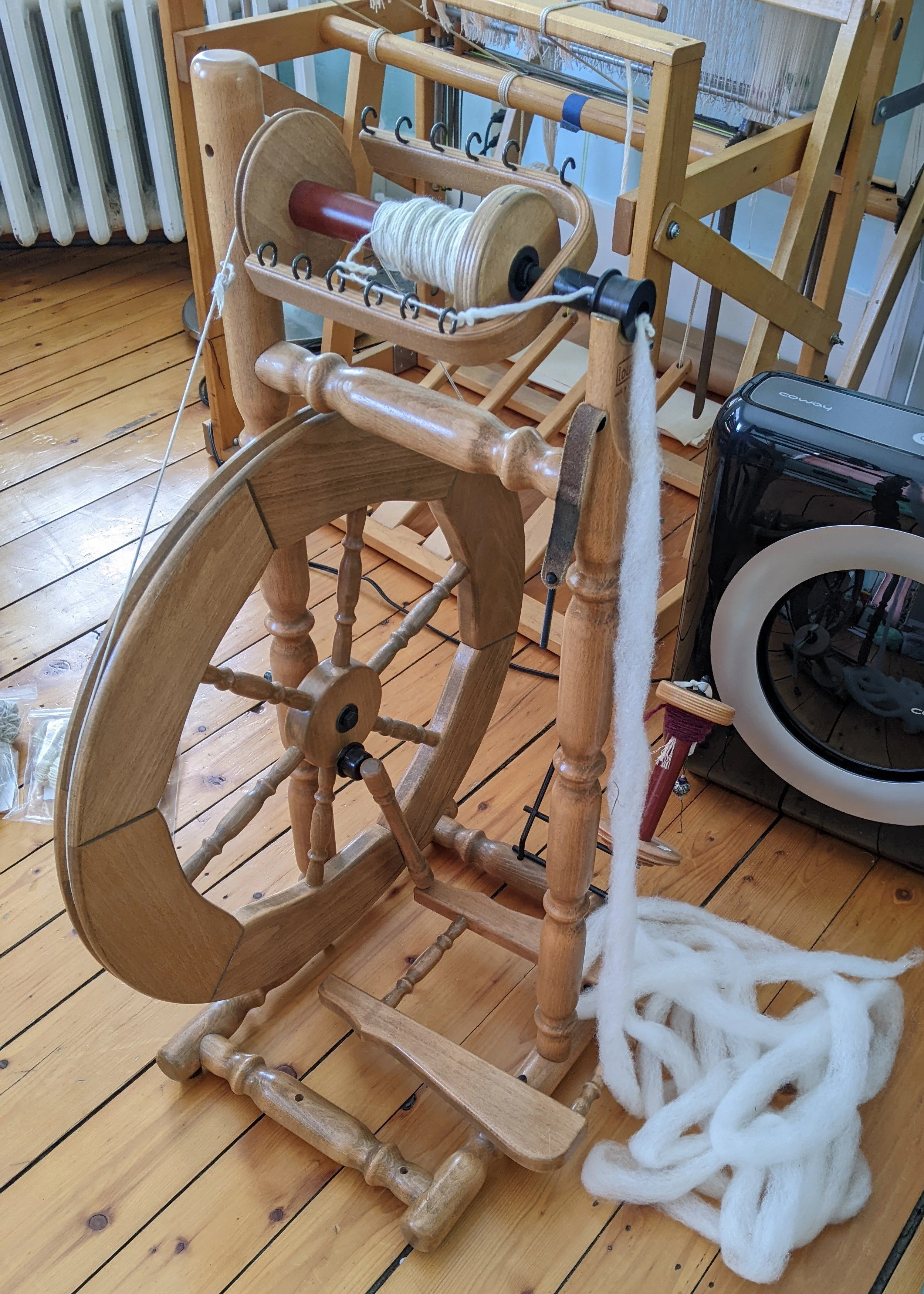

Spinning is the busy work that makes the woven cloth possible and the design take shape. All these different “threads” hang out in my head in a very sprawling imaginative space, while I spin the very real wool through my fingers and I get to ask myself that marvelous therapy question—what’s up with that?